I recently listened to this podcast called "How to be a (realistic) climate optimist" from Vox featuring Hannah Ritchie, deputy editor of OurWorldInData.org. Ritchie talks about how some of the things that we think about as climate action are actually not exactly effective climate action. Eating local or using plastic straws are brought up as examples. The real big sources of emissions, Ritchie points out, are things like the type of food we eat1. Where it comes from is negligible. How we travel has a big impact. Whether we drive, walk, or fly changes our emissions significantly.

However, Ritchie brings up something interesting along 21:30. Although she has her own opinions on what we should do about climate as a person, as a professional she refuses to involve herself in policy debates. She does not distinguish between policy and politics — they're all one and the same because joining one reduces her credibility as a scientist who focuses on climate change. She says that detractors will claim she has an agenda, and abstaining from political commentary allows her to eschew that.

Whether or not what Ritchie is saying is true is not what I want to focus on, however. What I do want to focus on is that she does call for politicians to call for fixing climate change, and that they should be able to use the data that scientists produce to inform the policy priorities they create. This is a reasonable ask.

However, most people are not weird, and do not have detailed policy preferences. When asked, they simply decide on the spot whether something is good or not. Ask someone a simple question like, "do you think that solar panels are good," and they would probably say "yes." Ask them something like "do you think that goat grazing is an acceptable method of under-panel grass trimming" and they might look at you like you came from Mars. Most people do not think about the climate all the time. Whether the weather is weird or not does impact them, but more in the sense that they may have gone on a walk last week when it was 60F instead of staying inside like the previous Thursday.

Climate activists seem particularly averse to "selling" their movement, perhaps because of all of the doom and gloom that climate news seems to bring. Constantly reading about how the oceans will rise and swallow the coasts and destroy all island nations certainly does not help optimism. I am not saying that all of that may happen, but when you come to someone claiming the apocalypse is befalling them, and that they must cease all normal operations to return to a zero degree world when life just seems kinda... normal? will get you few allies. Weirdos like myself who are already "in the weeds" 2 might join along, but most people just don't care! This isn't top of mind for them, it does not immediately affect them, and if you do not explain issues in the terms that people understand, they won't be interested in coming along with you.

I think a good example of this is the debate around liquified natural gas. Natural gas has a big marketing push behind it. Calling it clean natural gas is bizarre. It is not exactly clean, but it is cleaner, and while it is natural... so is oil. Regardless, many climate activists are very against having liquified natural gas terminals in the United States and are adamant that we must prevent any from opening and shut down any existing ones. Matt Yglesias brings this up in a recent blog post. Climate activists did not stop to think, hey, would blocking this reduce carbon emissions on a whole? Instead, they simply took that more LNG terminals = more emissions at face value, and moved on. But LNG terminals don't exist in a vacuum. Surely there is not unlimited demand for LNG terminals! Also, blocking LNG terminals might raise energy prices, which seems relatively bad for pro-climate policy. Training people to believe that pro-climate = more expensive seems like a failure of a plan!

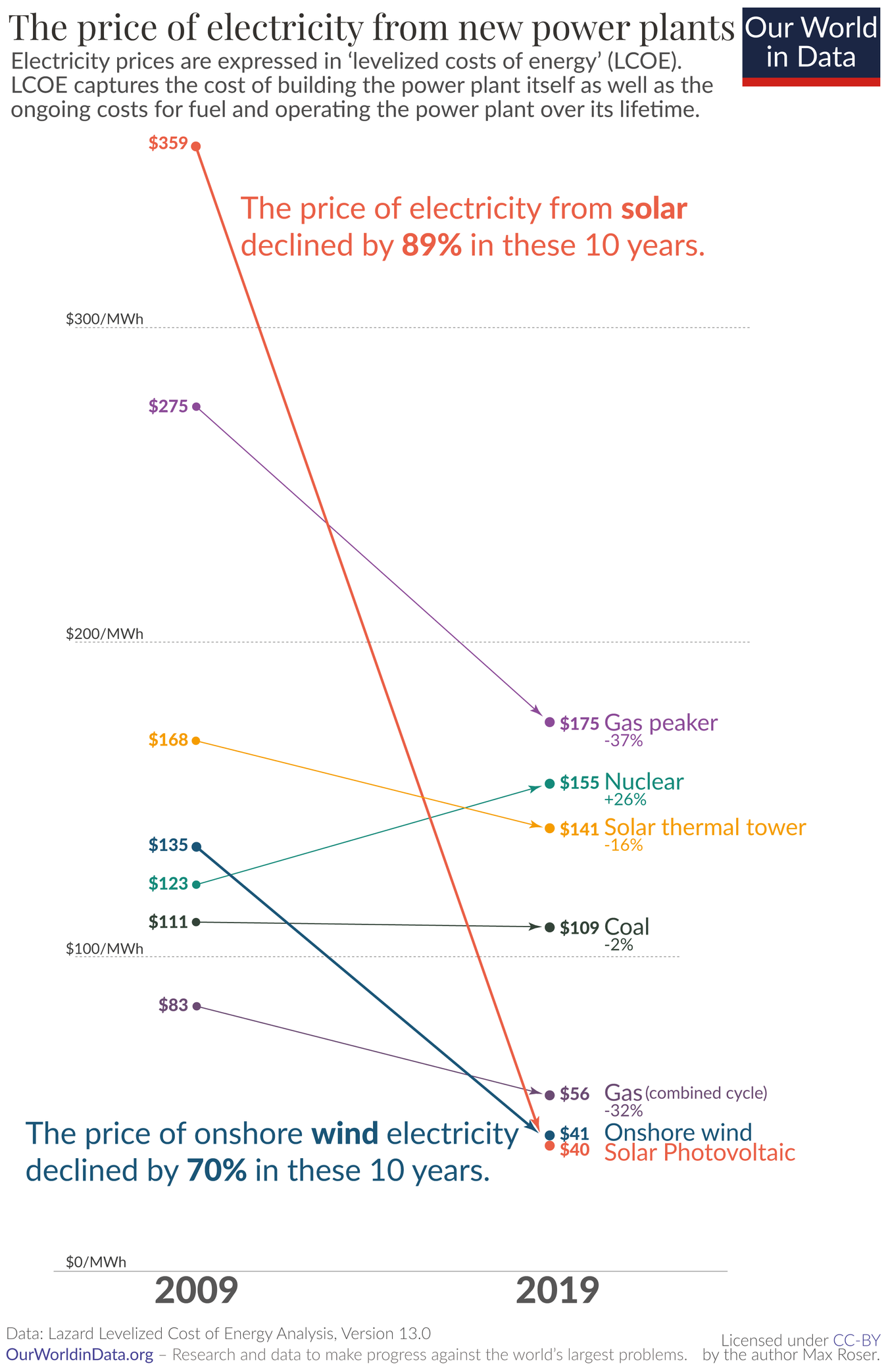

The messaging that people use to explain climate change seems like a problem with solutions. You just have to explain it to people in a way they understand. Instead of making it seem like solving the climate crisis requires you do to strange things like let food rot in a box in your kitchen or backyard or that you must drink out of a disgusting mushy paper straw or that you must pay $30,000 to build a solar panel on your roof, you could simply explain things in a way that normal people understand. Solving the climate crisis can save you money — solar and wind energy have cratered in price, and are now cheaper than coal or natural gas. We can cut red tape to increase investment in American workers by slashing obstacles to deploying clean energy. If the government backs nascent industries in renewable energy production, we can create new jobs at many income ranges. Backing these industries will stick it to oil super majors, who are fat on profits from low competition.

I just think that people do not think beyond their bubbles. In a vacuum, this is not really a concern. People have generally existed in their bubbles. But now, the bubble of Trumpian ideas is older and much more likely to vote. If your bubble is too small, you need to burst it from the inside and help those in the other bubble to join you beyond the cave. There are so many other things that could use normie-fication. Banning cars is a take completely beyond the pale. It immediately turns people off, making them into opponents. Banning zoning is another bizarre take (one that I have made!). Most people are normal, and do not think like (abstract) you. Empathize with them to explain the policy issues you think we have.

Note: I know I did not make two posts yesterday like promised. In sha Allah this week!

1 One popular environmental thing is reducing food waste. Ritchie brings this up during the podcast as well. This is something I am interested in — is reducing food waste actually an effective and easy way to reduce emissions? Perhaps. Composting is easy, if you like collecting food waste and ensuring it rots. According to the EPA, food waste comprises about 24 percent of municipal solid waste in landfills, but contributes an estimated 58 percent of released methane emissions. ↩

2 Good pun, huh...↩